Piano for Vocalists - Continuing Onward

This series of posts is intended for the vocalist who wants to acquire more skills at the piano, but may not currently have the means or access to piano lessons. The tips and techniques discussed in these posts should not be taken as a piano curriculum. They are specifically focused on giving the vocalist the skills they need to use the piano most effectively as a singer. While the best attempt at providing good piano technique will and should always be made, these posts are no substitute for actual lessons with a good piano teacher.

As you gain more skill there will be opportunity to do more with the piano which will therefore make it easier for to work on your literature. Moving into full octave scales is one of the first things that should be done. The fingerings for the various scales require more than the standard 1-2-3-4-5 of the five finger scales. The finger crossings to facilitate playing all eight notes are the most obvious requirements. This technique is useful for most melodies that vocalists need to sing at some point. You may have already done such finger crossing work while working through some melodic lines.

Let’s start with C Major. It is actually useful to start with the scale in contrary motion as this allows the hands to practice the crosses at the same time (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Begin with both thumbs on Middle C and play 1-2-3. As the third fingers are being played cross the thumbs under the hands to play the next note. This then sets the hands up to complete an octave by playing 1-2-3-4-5. The second half of the scale reverses the pattern, by moving the fingers above the thumbs to play the third finger and complete the octave. Once the contrary motion is comfortable you can start the parallel (Figure 2). Skills are one of the best ways to build up agility in the fingers, and the parallel motion is good for working the independence of the hands.

Figure 2

With my students I often find it helpful to drill to each cross as shown in Figure 3.

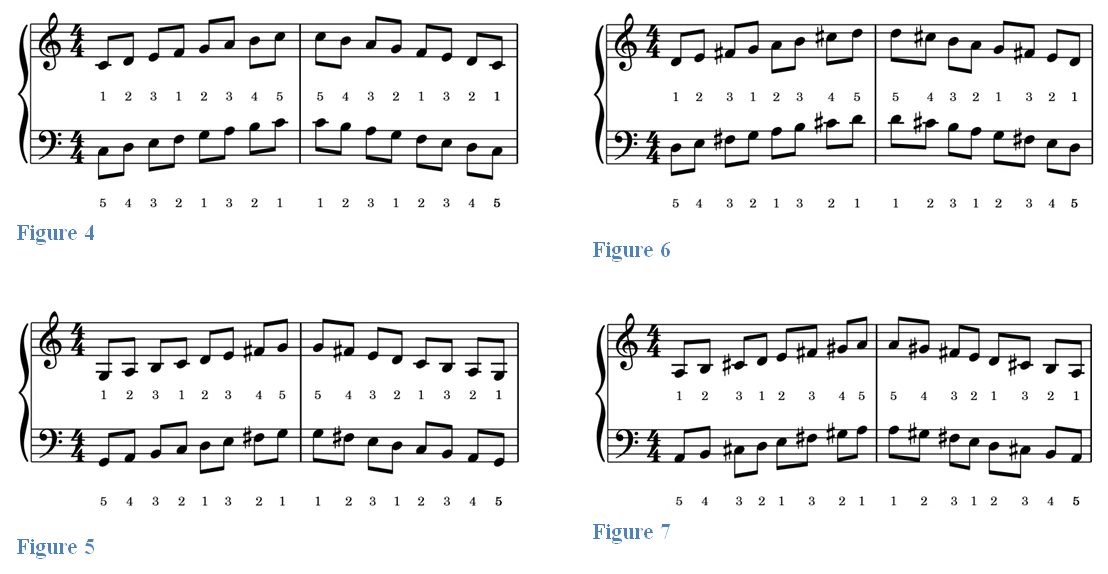

This fingering works for the C, G, D, A, and E Major scales with adjustments for the black keys (Figures 4-8). F Major is similar with a slight modification for the B-flat (Figure 15). The rest of the scales begin with different fingers and can have different fingerings depending on the method book or resource one uses. Figures 9-14 include the ones I use myself.

Once the one octave is comfortable, more octaves can be added by making a second cross from Ti to Do (Figure 16).

It is also good to continue to experiment with wider intervals, both melodically and harmonically. For intervals that are wider than a fifth the most common way to handle them is to play them with the first and fifth fingers. This will serve for many instances, though it is also good to experiment with different combinations as discussed in the melody post. To provide context it can be good to go back to sightreading, specifically lines of different instruments, because those introduce interesting note combinations and patterns that aren’t necessarily as common in piano or vocal music. Some of the leaps that are easily played on the violin for example can provide a challenge to play on the piano. As vocal lines can often have complicated leaps as well, being able to play wide intervals with a variety of fingerings is essential.

To gain more facility and agility in the fingers I also recommend finding actual piano exercises. Ones from “The Virtuoso Pianist” by C. L. Hanon are particularly good because they explore common patterns and fingers and have a logical progression to them. I have also used some of these patterns as vocal warmups, so that is an added benefit. The fact that they are also easily available on IMSLP helps as well.

My entire philosophy when it comes to a vocalist’s piano skills comes back to vocal warmups. A good singer should be readily able to play a variety of different warmups with one hand at the minimum, two ideally. And if the vocalist can play the melodic aspect of the warmup in the right hand while improvising some sort of accompaniment in the left all the better. For the latter goal it is good to get a book of common warmups and find a way to incorporate some of the common accompaniment patterns into them as chord progressions are explored.

An additional step to take is to expand on the multipart work we covered in the melody post. Finding four part choral literature and working on playing various combinations of the parts is an excellent skill to have. Doing so allows you to see how your part fits with each of the other vocal lines, which can provide a wealth of information. We already started with the part that is closest to yours. Go the other extreme and work on playing that part that is furthest from yours. This can be a real challenge at first, depending on the layout of the score.

My goal is always to be able to play all four parts at tempo, but that is honestly out of reach for me most of the time, especially when sightreading. The next step down should be the ability to play all of the parts slowly to at least have a grasp of the harmonies. Then work on being able to play two parts at tempo in each hand separately.

Following all of the steps lined up in this series will not only arm you with the skills to make you a better vocalist, they will also help to make you a more well-rounded and versatile musician.